Stars & Icons

5

Stars & Icons5

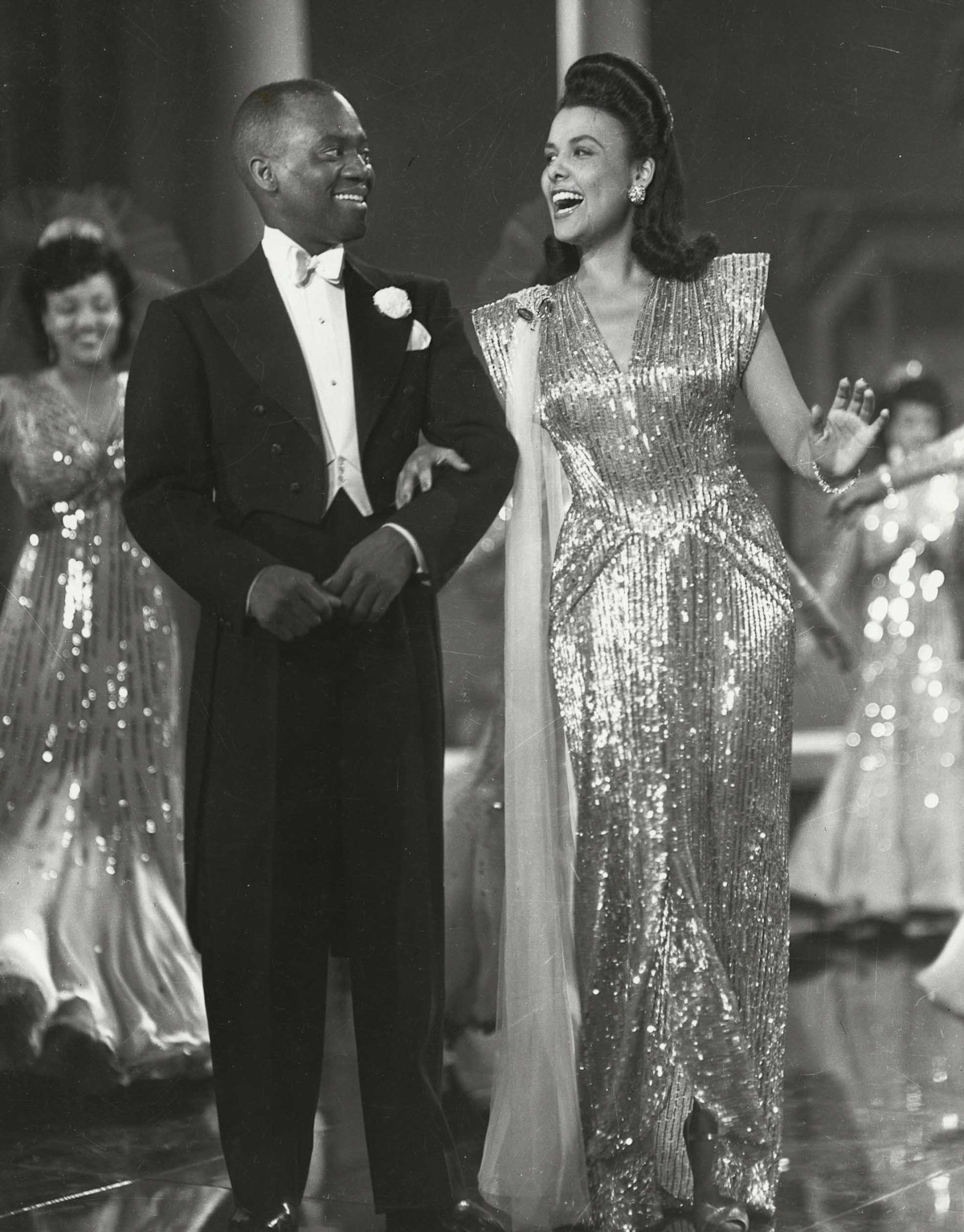

Bill Robinson and Lena Horne in Stormy Weather (1943)

Theme Overview

Hallelujah (1929), Cabin in the Sky (1943), Stormy Weather (1943), Carmen Jones (1954), and Porgy and Bess (1959) are iconic all-Black-cast musicals directed by white directors and produced by Hollywood studios. The performances by artists such as Harry Belafonte, Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, the Nicholas Brothers, and Ethel Waters in these classic films are often the first things to come to mind when we think of Black cinema, African American performers, and Black Hollywood.

Featured Essay

Hattie McDaniel: Talent, Drive, Audacity, Agency

Scroll To Explore

In this excerpt from his essay for Regeneration’s companion volume, film historian Donald Bogle looks at the complex careers of Hattie McDaniel and other Black actors working in Hollywood in the first half of the twentieth century.

Jean Harlow and Hattie McDaniel in Saratoga (1937), production still. Courtesy Margaret Herrick Library.

By the time Hattie McDaniel (1893–1952) appeared in Gone with the Wind (1939), she had worked in films for seven years and had an entertainment career that stretched back decades. After GWTW, she would find herself still struggling for challenging roles within the confines of the studio system. In the end, with well over a hundred films to her credit, her career would encapsulate some of the complexities and complications faced by Black actors working in Hollywood in the first half of the twentieth century. McDaniel most often played characters that conformed to the mammy stereotype: larger, often darker Black women who were desexed and deglamorized. As giddy, eager-to-please mother surrogates, her characters were often trusted confidantes who were there to comfort, aid, assist, and reassure troubled, vexed, or confused white characters.

Hattie McDaniel with her green Packard Twelve, ca. 1940. Courtesy Margaret Herrick Library; Hattie and Sam McDaniel Collection

Yet in film after film, little was known about the lives of her characters. If another perspective were to be shown, it had to be done covertly, by getting inside or under the dialogue to create a knowing subtext. For Hattie McDaniel, a key signal to such a subtext was foremost her attitude. Then there was her powerful, thundering voice. Once you heard her speak, you knew she was born to give orders, not take them. As the maid Hilda in The Mad Miss Manton, she fusses and fumes with the socialite friends of her on-screen employer Barbara Stanwyck. “Hilda,” says Stanwyck, “Miss Beverly is our guest.” “I didn’t ask her up,” snaps McDaniel. McDaniel used clever dialogue to establish herself as the power broker, the social arbiter, the woman who sets the standards and calls the shots, making key decisions and declarations that overturn traditional social/racial roles while seemingly observing them. For her performance in Gone with the Wind, McDaniel was able to inject covert messages as she had in previous films. Though her character supports the values of the dominant culture, she repeatedly berates Scarlett and questions her motives, understanding her far better than Scarlett’s mother, Ellen O’Hara. Through the force of her personality, she has an agency—seen in everything she does, from her posture to the way she moves—that the film cannot explain.

From left: Hattie McDaniel, Oscar Polk, and Ben Carter during the filming of Gone with the Wind (1939), production still. Courtesy Margaret Herrick Library; Hattie and Sam McDaniel Collection

McDaniel became the first African American to win the Academy Award, here for Best Supporting Actress. In her acceptance speech, she said she hoped she would always be a credit to her race and the motion picture industry. The speech was all the more poignant because at the ceremony McDaniel was not seated at the table with the other stars of the film. Nor had McDaniel been permitted to attend the film’s premiere in Atlanta.

Hattie McDaniel (partially visible at lower edge) and Ferdinand Yober, at the banquet for the 12th Academy Awards, Cocoanut Grove, Ambassador Hotel, 1940. Courtesy Margaret Herrick Library.

Hattie McDaniel and her brother Sam in The Great Lie (1941), publicity still. Courtesy Margaret Herrick Library.

Full essay available in the Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 exhibition catalogue, available for purchase at the Academy Museum Store.

Donald Bogle, one of the foremost authorities on African Americans in film, is the award-winning author of nine books, including the groundbreaking Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films(5th ed., Bloomsbury, 2016); the critically acclaimed Dorothy Dandridge: A Biography(Amistad, 1997); the evocative social history Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams: The Story of Black Hollywood(Ballantine, 2005); Heat Wave: The Life and Career of Ethel Waters(Harper, 2011); Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers(Running Press, 2019); and Brown Sugar: Over One Hundred Years of America’s Black Female Superstars(Continuum, 2007), which was adapted by Bogle into a PBS docuseries. He teaches at the University of Pennsylvania and at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts.

Essays

Article

In the Gallery: Stars and Icons

The gallery explores the complexities of being a Black person in the film industry, highlighting essential artists while sharing insight into what life was like away from the spotlight.

Article

Hattie McDaniel: Talent, Drive, Audacity, Agency

Donald Bogle looks at the complex careers of Hattie McDaniel and other Black actors working in Hollywood in the first half of the twentieth century.

Article

African American Home Movies

Examine how African American home movies affirmed Black lives during a period when most commercial productions treated Black subjects in a stereotypical and marginal manner.

Freedom Movements6

Scroll To Explore