Race Films

3

Race Films3

Reform School (1939)

Theme Overview

“Nothing has done so much to awaken the race consciousness of the colored man in the United States as the motion picture. It has made him hungry to see himself as he has come to be.” —William D. Foster, 1913

Between 1915 and 1948, more than 150 independent companies produced and distributed Black-cast movies, or “race films,” which offered an array of stories and roles for Black actors and were aimed at Black audiences. Black-owned production companies made melodramas, westerns, comedies, adventure films, and more.

The third gallery in Regeneration, “Race Films,” considers the legacy of some of these early image makers. Lincoln Motion Picture Company, the Micheaux Film Corporation, and white-owned production studios such as the Norman Film Manufacturing Company were some of the earliest forerunners. While many films by these production companies are thought to be lost, surviving posters offer a glimpse into this tremendously creative world.

Featured Essay

Reform School

Scroll To Explore

In this excerpt from her essay for Regeneration’s companion volume, film scholar Ellen C. Scott considers how a late-period race film examined the wrongs of the criminal justice system.

An established and prolific mode of production in the silent cinema era, race filmmaking often portrayed aspirational narratives of Black success while also revealing, if sometimes inadvertently, the realities of racial injustice and poverty. While race films saw a decline in the late 1920s with the arrival of sound and associated increased costs, Reform School (1939), made by white producers who could get the capital to finance it, continued the race film’s unique mode of engagement with the complexities of the Black community.

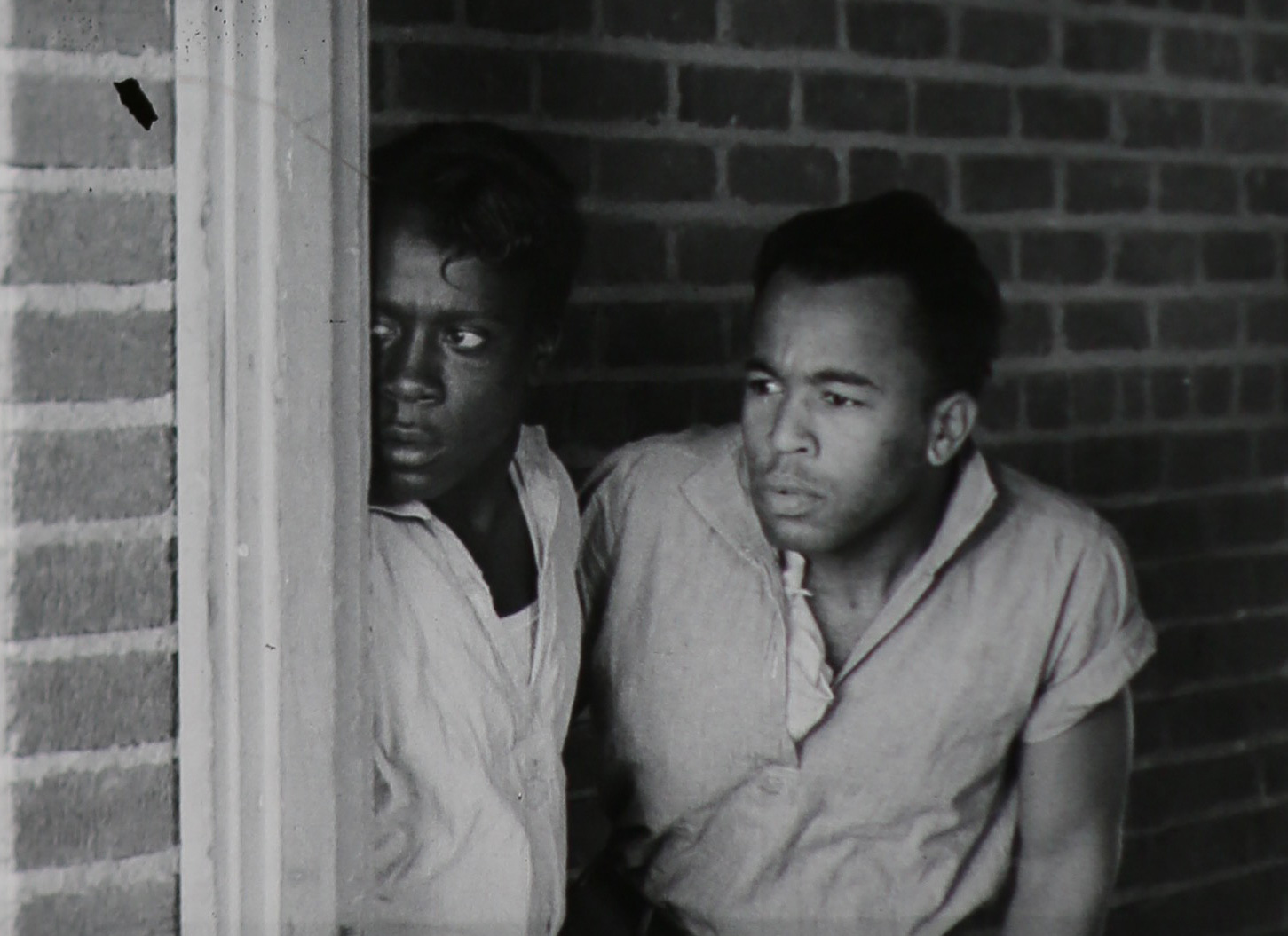

The Harlem Tuff Kids in Reform School (dir. Leo C. Popkin, 1939), film still

Harry M. Popkin and Leo C. Popkin’s Million Dollar Productions, the company that produced Reform School, is notable for having consistently worked closely with Black community members to make race films that reflected social issues such as criminalization, justice denied, fugitivity, and Black-on-Black crime. [1] The Popkins broached racial oppression but did so without pessimism. They maintained good relations with the Black press and the white trade press, eliciting consistently positive reviews in Variety and regular coverage in the Black press. They also sold their films to both Black and white theaters. [2] Reform School tells the story of Freddie Barton (Reginald Fenderson), a Black teenager convicted of a petty offense who consequently cannot find work and falls back into a life of crime. When Mother Barton (Louise Beavers), an understanding and tough probation officer, witnesses Freddie in agony as he’s confined to reform school under a cruel superintendent named Stone (Edward Thompson), she works to have him removed and takes over as superintendent. Barton places the troubled youth on an honor system to teach them to respect the law rather than fear it. The boys take advantage of her at first, but eventually they grow to respect her. So successful are Barton’s policies that they are implemented statewide, and the boys secure good jobs upon leaving reform school.

Louise Beavers in Reform School (dir. Leo C. Popkin, 1939), film still. Courtesy Academy Film Archive.

Barton, who embodies the “lifting as we climb” ideals of the historical Black women’s club movement, condemns the criminal justice system for the ways that it imperils “her” boys. [3] Dressed in furs and high hats as matron of the reform school—a far cry from the mammies Beavers often played in white Hollywood films—Barton takes on all the dignity of middle-class Black uplift that we might expect from Mary Church Terrell. [4] In transforming Barton into the upstanding “mother” to a community of Black boys, the film represents the important roles that Black women have historically played in their own communities, roles that Hollywood largely erased. Reform School admits of the violence that haunts Black life but believes more wholeheartedly in the goodness of Black youth and the necessity of removing the punitive edge of reform than do many crime dramas today. The film’s history provides a rare window into the unique filmmaking practices of one of the only production companies in Hollywood making race films, one that took its production techniques from the studios but its cues on racial representation from members of the Black community.

Full essay available in the Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 exhibition catalogue, available for purchase at the Academy Museum Store.

[1] The Well (1951)—a later film from the Popkins that treats race riots with a singular combination of force and racial delicacy—is a good example of this.

[2] For more on their being marketed to white theaters, see “‘Bargain with Bullets’ Is Cinematic Bargain,” New York Age, December 4, 1937. The author states that the film was shown to the Loew’s theater chain.

[3] See Deborah Gray White, Too Heavy a Load: Black Women in Defense of Themselves, 1894–1994 (New York: Norton, 1999).The concept of“lifting as we climb” has been an ethos guiding Black feminist political activism for generations and was also the motto of the National Association of Colored Women.

[4] Mary Church Terrell (1863–1954) was an influential Black suffragist who devoted her life work to the idea that Blacks could help diminish white racism by advancing themselves through work, education, and community organizing.

Ellen C. Scott is associate professor of cinema and media studies and associate dean of the School of Theater, Film and Television at UCLA. Her research focuses on the meanings of media in African American communities and the relationship of media to the struggle for racial justice and equality. She is the author of Cinema Civil Rights: Regulation, Repression, and Race in the Classical Hollywood Era(Rutgers University Press, 2015). She is currently working on two projects, one exploring Black women film critics and another examining the history of slavery on the American screen, which has received a grant from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Academy Scholars program.

Media Gallery

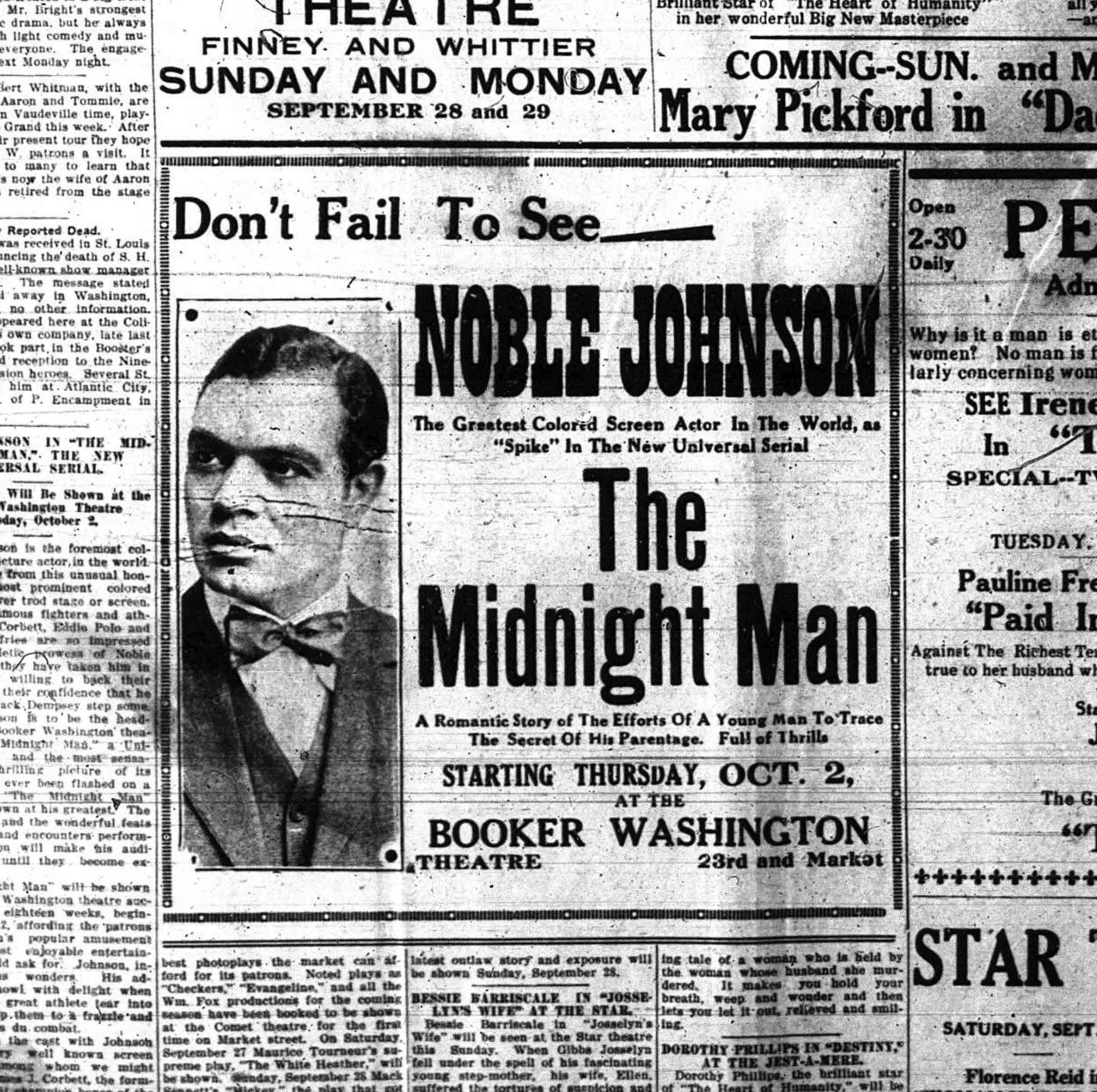

Advertisement for the film serial The Midnight Man (1919), featuring Noble Johnson, in the St. Louis Argus, 1919 The serial played at the 506-seat Booker T. Washington Theatre in Saint Louis.

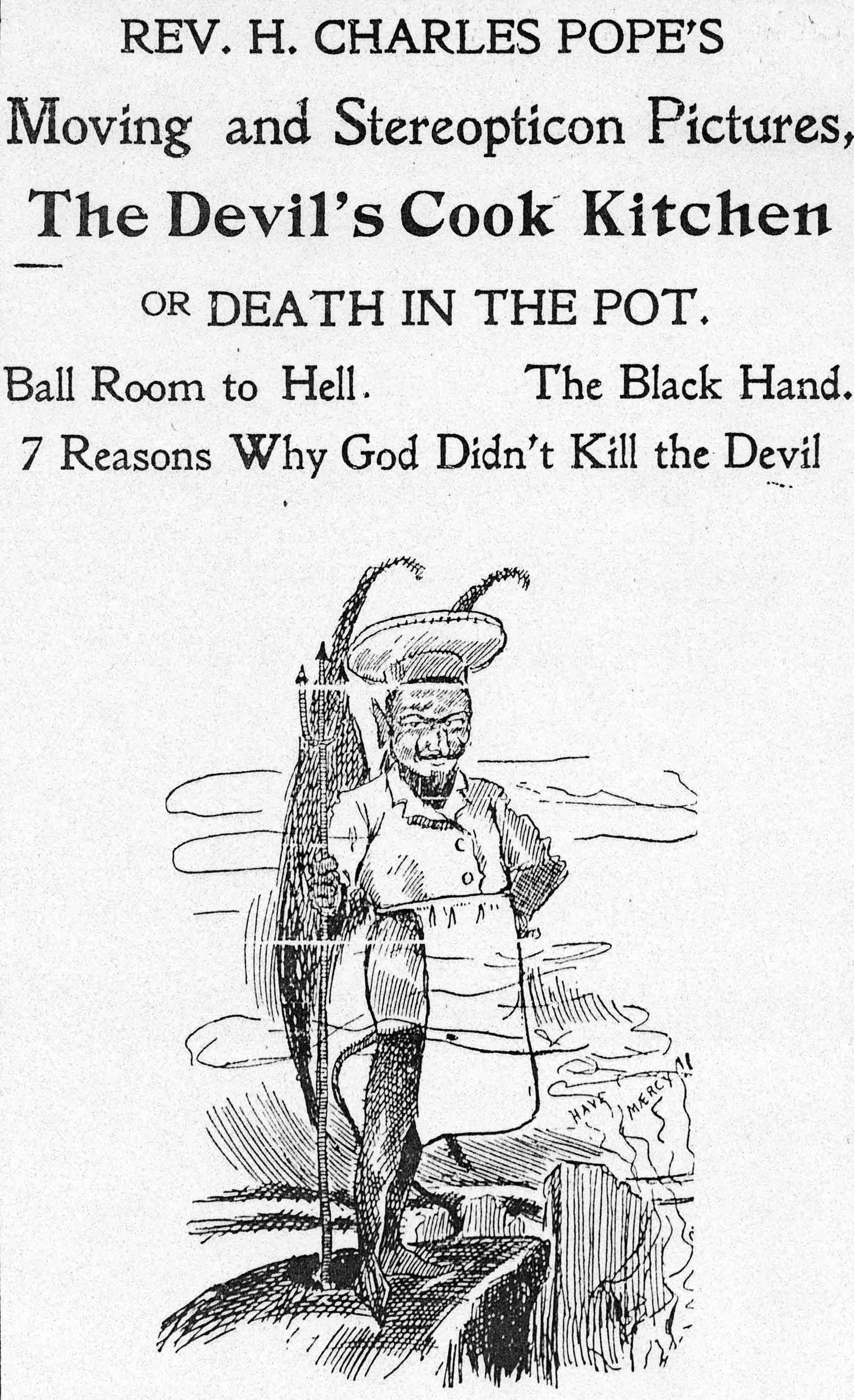

Advertisement promoting H. Charles Pope’s The Devil’s Cook Kitchen (1905) in the Indianapolis Freeman, 1905

Glenn Ligon’s Double America 2, 2014, © Glenn Ligon, courtesy of the artist

Regeneration (1923)

Essays

Article

In the Gallery: Race Films

Between 1915 and 1948, more than 150 independent companies produced and distributed Black-cast movies, which offered an array of stories and roles for Black actors and were aimed at Black audiences.

Article

Spectatorship and the Black Press

Explore the role of the Black press in the emergence of African American cinema.

Article

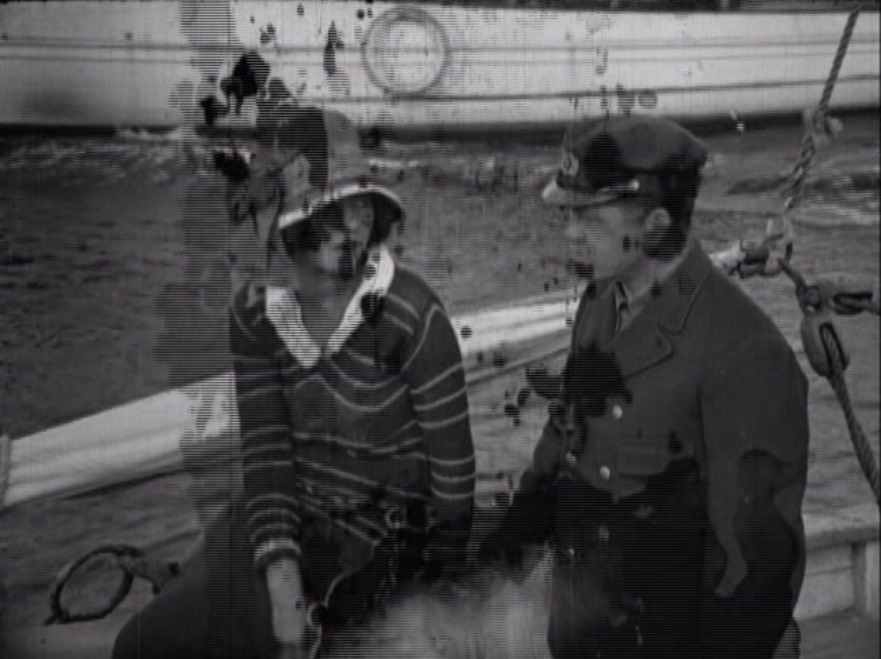

Lobby cards, Regeneration (1923)

Regeneration, billed as a South Seas thriller-romance, became a huge hit with both Black and white audiences. Beyond lobby cards and production stills, only a few minutes of this film survive.

Article

Object Spotlight: Balcony Seating Only

Gary Simmons’ (b. 1964) sculpture is inspired by a historical photograph of the exterior of a segregated theater in Anniston, Alabama.

Article

Reform School

In this excerpt from his essay for Regeneration’s companion volume, film scholar Ellen C. Scott considers how a late-period race film examined the wrongs of the criminal justice system.

Music and Film4

Scroll To Explore