Introduction

1

Introduction1

Something Good – Negro Kiss (1898)

Theme Overview

"History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history."—James Baldwin, 1980 [1]

The first of Regeneration’s seven galleries, “Introduction,” offers visitors a contemplative gloss on the exhibition’s broader themes through a quartet of moments: a quote, a work of contemporary art, and two versions of the same short film.

Featured Essay

What Is Black Cinema?

Scroll To Explore

In this excerpt from their essay for Regeneration’s catalogue, the show’s cocurators, Doris Berger and Rhea L. Combs explore a question at the heart of the exhibition: What is Black cinema?

In an interview that appears in this volume, the director Charles Burnett recalls having heated debates about the question of what constitutes a Black film while studying at UCLA in the 1970s: “We didn’t come to a conclusion, but it was easier to say what was not a Black film.” As the film historian Michael Boyce Gillespie has observed, “The idea of Black film is always a question and never an answer.” [1] Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 also does not attempt to provide a definitive answer, although the question drives this project, which accepts the premise that Black cinema is not a genre; nor is it tied to any specific era. Regeneration explores the myriad ways in which Black artists, filmmakers, and critics navigated an often prejudiced and segregated system over seven decades, either finding ways to work within dominant industry structures or choosing to develop their own dynamic creative communities.

The Chicago-based entrepreneur William D. Foster, for example, widely considered one of the first Black film producers, recognized the power of the moving image early on, writing in 1913, “Nothing has done so much to awaken the race consciousness of the colored man in the United States as the motion picture. It has made him hungry to see himself as he has come to be.”[2]

Uplift and Visual Education

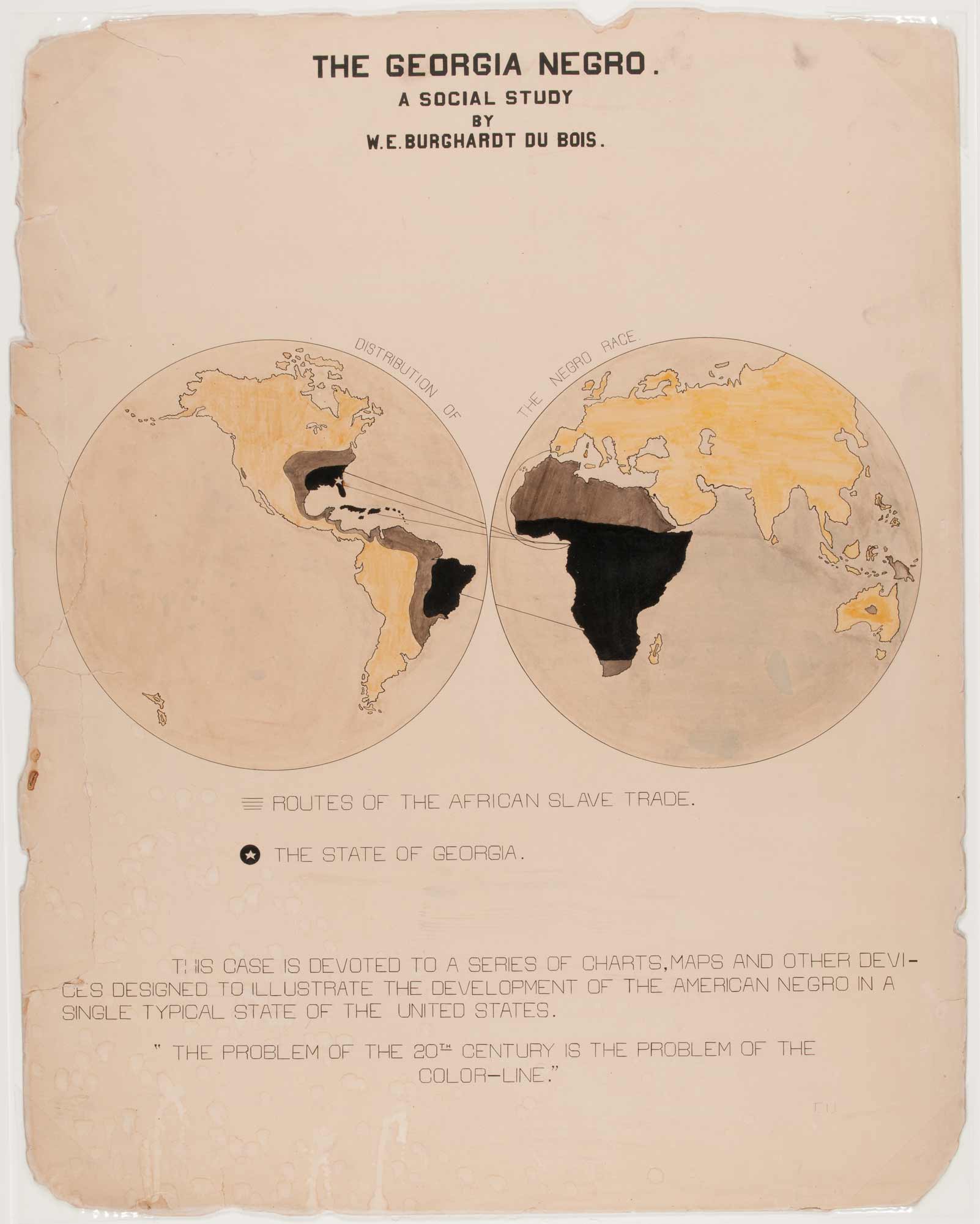

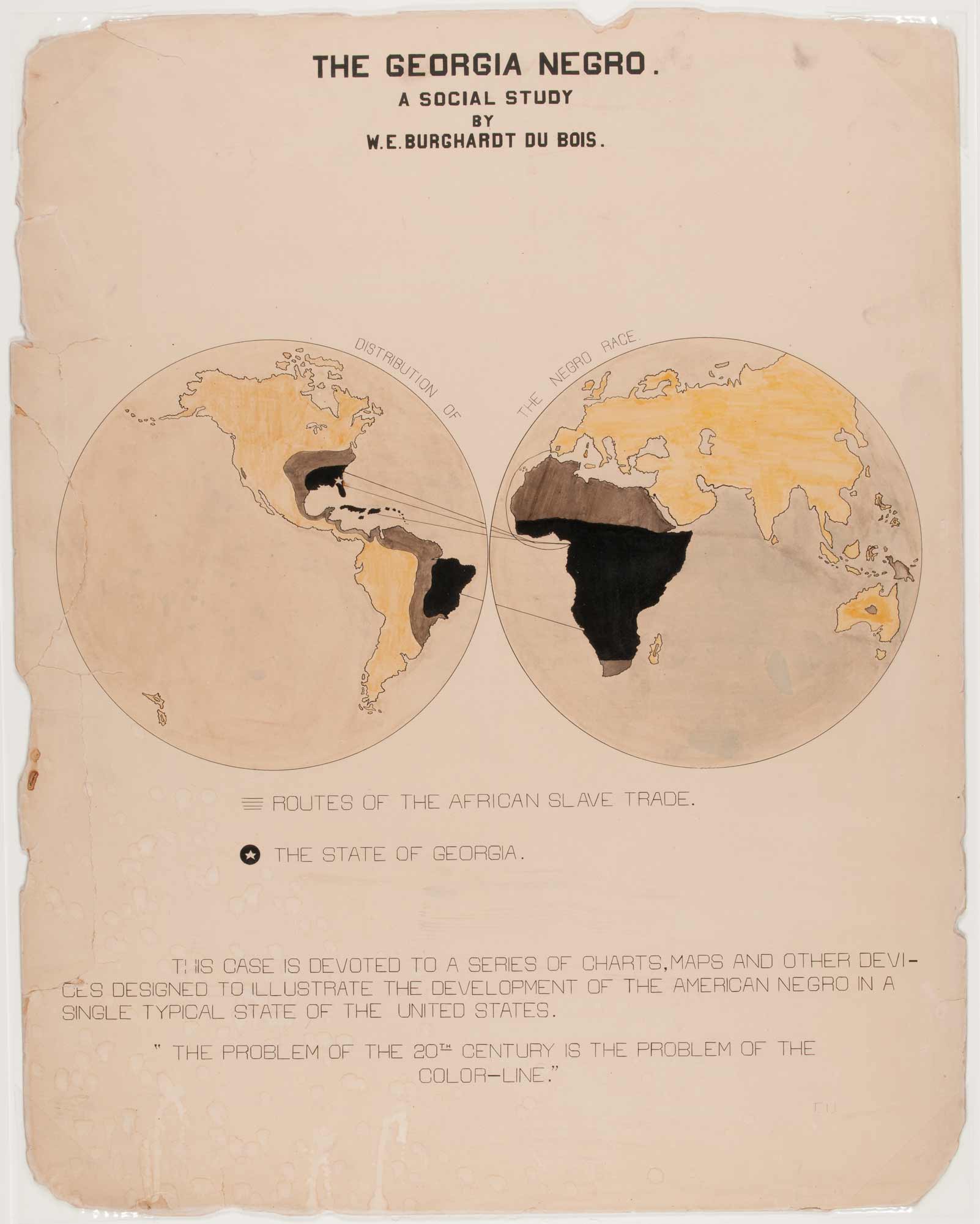

W. E. B. Du Bois, diagram from The Georgia Negro: A Social Study, 1900. The diagram illustrates African slave trade routes, with the state of Georgia starred. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Daniel Murray collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-33863. Photo: Library of Congress http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.33863

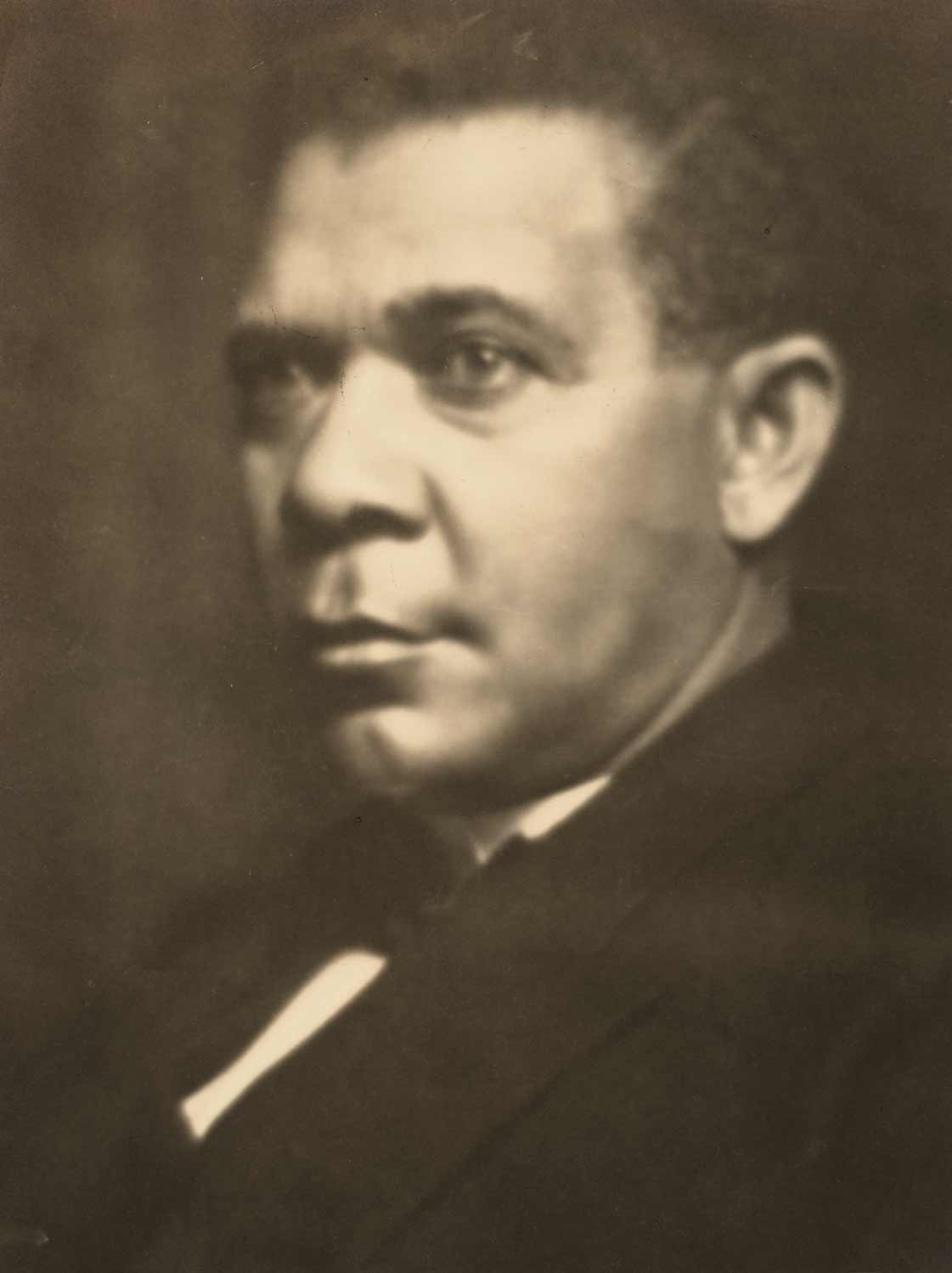

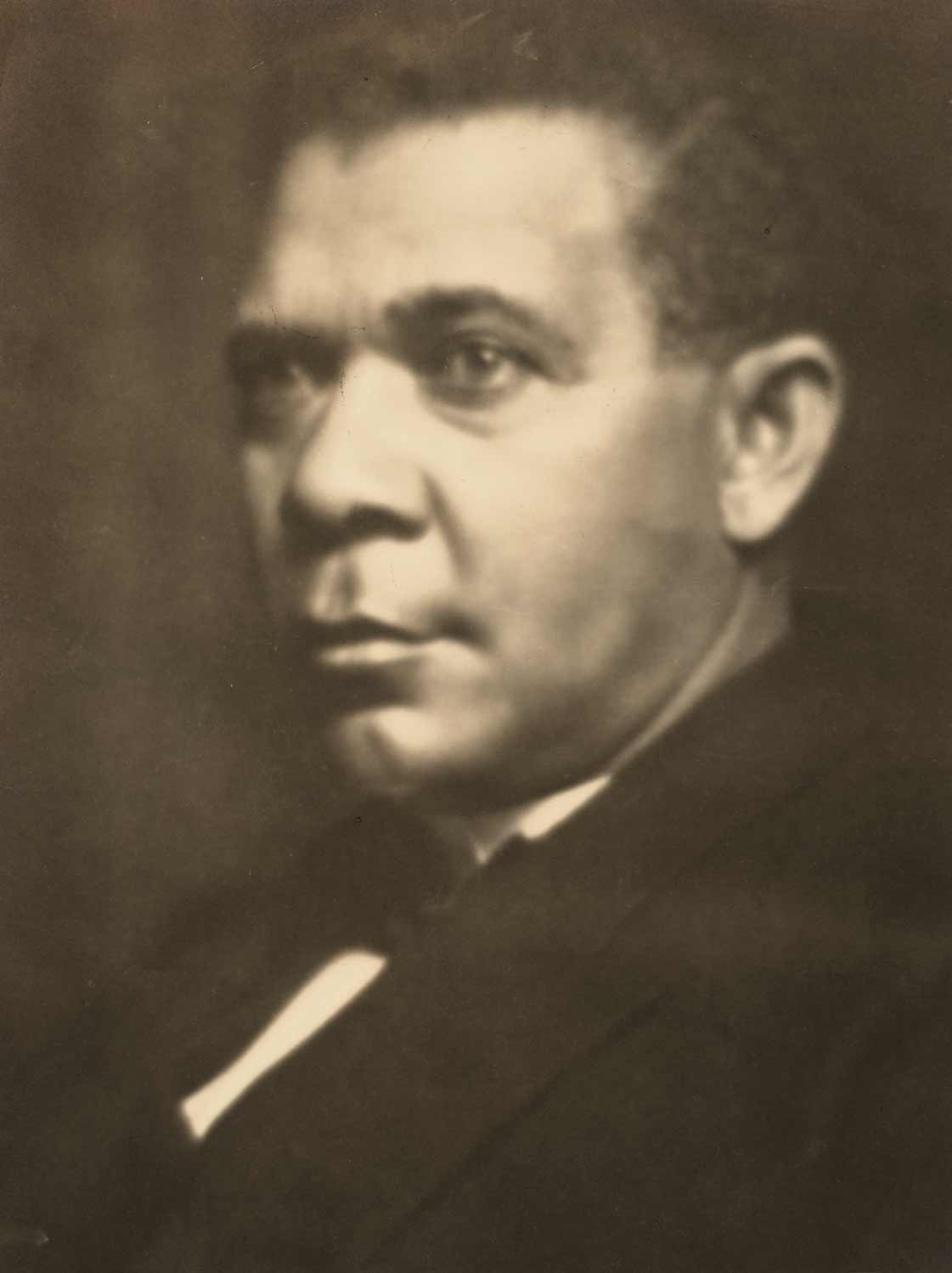

C. M. Battey (American, 1873–1927), Booker T. Washington, ca. 1908, gelatin silver print, 9 1/4 × 6 3/4 in. (23.5 × 17.1 cm). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2009.37.3. Photo: Smithsonian Institution Open Access.

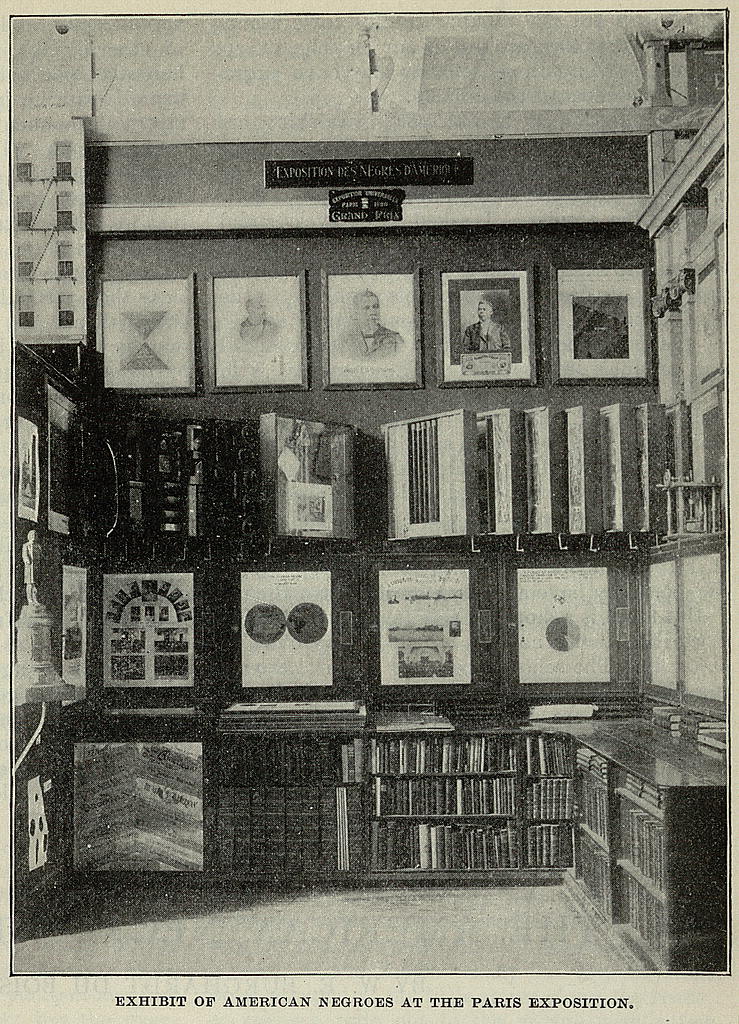

For the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, W.E.B. Du Bois curated the Exhibit of American Negroes, for which he created a display of the “small nation of people” through a series of books, 363 photographs of African Americans, and colorful hand-drawn illustrations showing off “Negro progress” in a variety of areas, including education, agriculture, and business. [3] This approach of presenting a “narrative of Black agency” [4] reflected the attitudes of many African Americans who were deeply invested in offering the world a respectable view of Black progress and self-reliance.

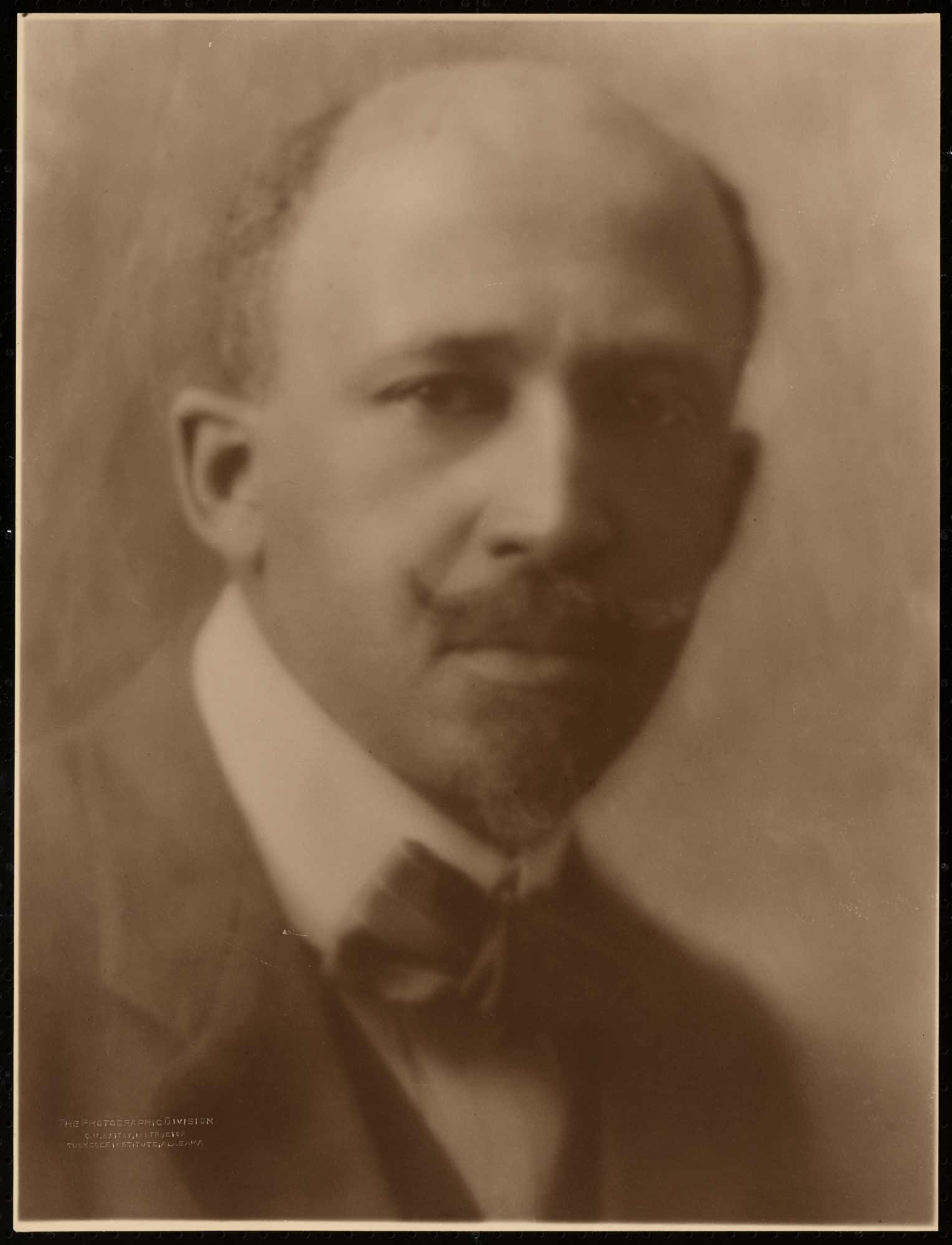

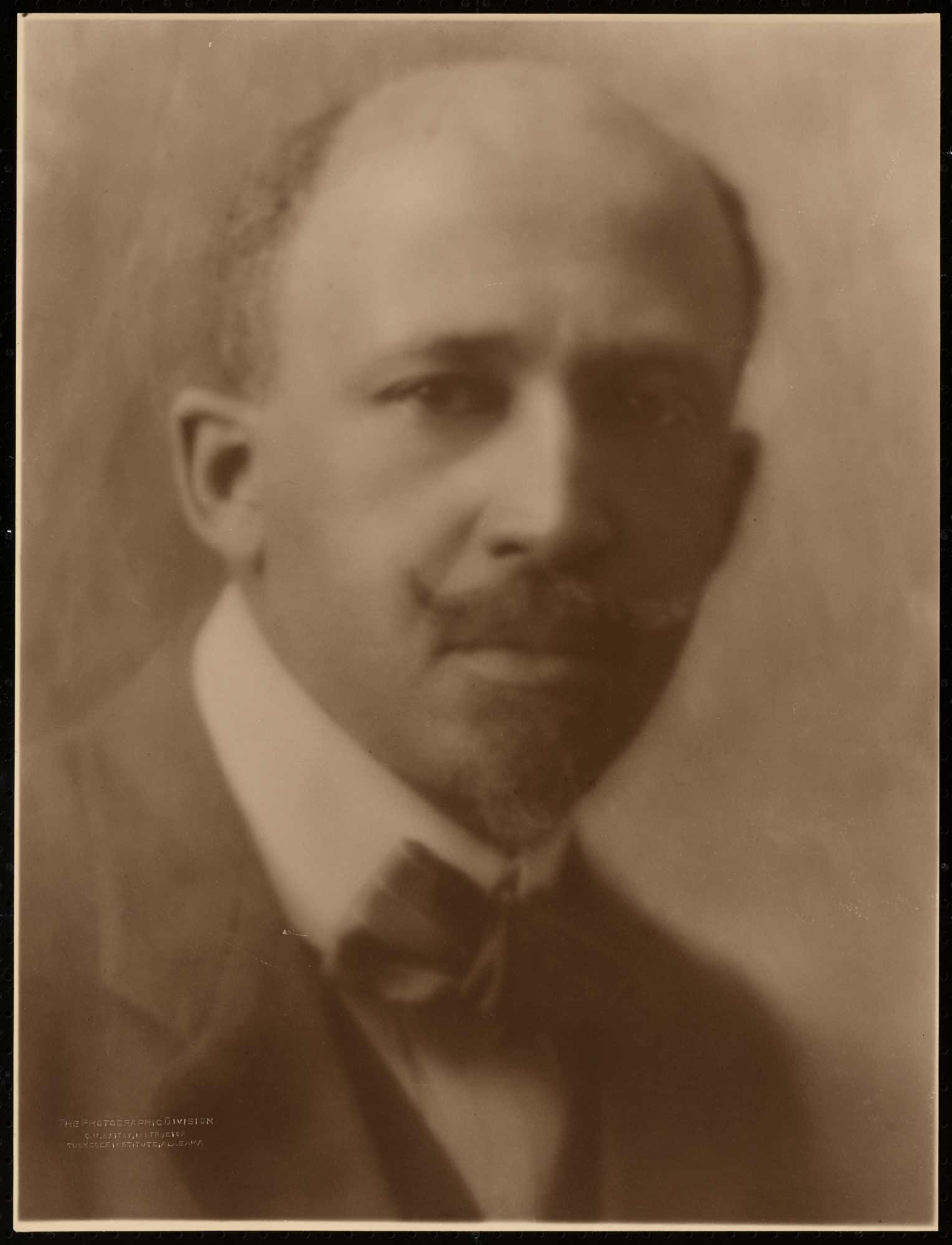

C. M. Battey (American, 1873–1927), W. E. B. Du Bois, 1918, silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper, 13 5/8 ×10 5/16 in. (34.6 × 26.2 cm). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2009.37.3. Photo: Smithsonian Institution Open Access

Booker T. Washington, the principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University), was less vocal than Du Bois in publicly condemning racism, believing that hard work, self-determination, and a vocational education were sufficient counters to white supremacy. Wielding significant influence, particularly as a founding member of the National Negro Business League, Washington used his affiliations with powerful white philanthropists such as the Carnegies and the Rockefellers to help raise money for small schools throughout the South. When asked to support the showcase of American Negroes at the Paris Exposition, [5] Washington said he believed that this project would help change minds about the role and legacy of African Americans.

Historians have long recognized the different approaches of Du Bois and Washington to further African American progress, but there were times in their respective careers when the pair were aligned in their efforts. At the very least, one thing they had in common was a dedication to that cause and a recognition of the important role that the new technologies of photography and moving pictures played in these efforts.[6]

Full essay available in the Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 exhibition catalogue, available for purchase at the Academy Museum Store.

[1] Michael Boyce Gillespie, Film Blackness: American Cinema and the Idea of Black Film (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 16.

[2] William Foster [Juli Jones Jr., pseud.], “News of the Moving Picture,” Freeman, December 20, 1913.

[3] Du Bois called the project “an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.” Quoted in David Levering Lewis and Deborah Willis, introduction to A Small Nation of People: W. E. B. Du Bois and African American Portraits of Progress (New York: Amistad, 2003), 18. [4] Aldon Morris, “American Negro at Paris, 1900,” in W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America; The Color Line at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, ed. Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert (Amherst: W. E. B. Du Bois Center, University of Massachusetts; New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2018), 27.

[5] Lewis and Willis, introduction to Small Nation of People, 16.

[6] While Washington did not choose to combat white supremacy through agitation and protest, he did understand the power of representation. Prior to his death in 1915, he was seeking funding to turn his 1901 memoir Up from Slavery into a film. Washington’s protégé Emmett Scott pushed on with the film The Birth of a Race in 1918, which, despite being distorted by its investors, was an attempt to challenge the imagery brought forward by D. W. Griffith in The Birth of a Nation (1915). Henry Louis Gates Jr., foreword to Separate Cinema: The First 100 Years of Black Poster Art, edited by John Duke Kisch (London: Rare Art Press, 2014), 12. See also Thomas Cripps, “The Birth of a Race Company: An Early Stride toward a Black Cinema,” Journal of Negro History 59, no. 1 (1974): 28–37.

Doris Berger

Doris Berger is vice president of curatorial affairs at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. She was previously a Getty postdoctoral fellow; a curator at the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles; and director of the Kunstverein Wolfsburg, Germany. Berger curated numerous art and film exhibitions, including Light & Noir: Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood, 1933–1950 (Skirball, 2014), and Isaac Julien: Baltimore (Academy Museum, 2022). She cocurated the Academy Museum’s inaugural exhibitions Stories of Cinema and Backdrop: An Invisible Art (both 2021). She is the author of Projected Art History: Biopics, Celebrity Culture, and the Popularizing of American Art (Bloomsbury, 2014). She has published essays in books and journals and has taught courses in art history, film, and gender studies in Austria and Germany.

Rhea L. Combs

Rhea L. Combs is director of curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, where she is responsible for the exhibitions and conservation teams. She has curated numerous exhibitions nationally and internationally, including Now Showing: Posters from African American Movies (2019–21), Watching Oprah: The Oprah Winfrey Show and American Culture (2018–19), and Everyday Beauty: Photographs and Films from the Permanent Collection (2016–19) for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where she previously served as supervisory curator of photography and film and director of the Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts. Her writings on African American cinema, Black women filmmakers, visual aesthetics, photography, and other topics have appeared in anthologies, academic journals, and numerous exhibition catalogues. She has lectured in the United States and abroad and has taught courses on visual culture, film, race, and gender.

Media Gallery

C. M. Battey (American, 1873–1927), W. E. B. Du Bois, 1918, silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper, 13 5/8 ×10 5/16 in. (34.6 × 26.2 cm). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2009.37.3. Photo: Smithsonian Institution Open Access

Glenn Ligon’s Double America 2, 2014, © Glenn Ligon, courtesy of the artist

W. E. B. Du Bois, diagram from The Georgia Negro: A Social Study, 1900. The diagram illustrates African slave trade routes, with the state of Georgia starred. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Daniel Murray collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-33863. Photo: Library of Congress http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.33863

C. M. Battey (American, 1873–1927), Booker T. Washington, ca. 1908, gelatin silver print, 9 1/4 × 6 3/4 in. (23.5 × 17.1 cm). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2009.37.3. Photo: Smithsonian Institution Open Access.

Installation view of the Exhibition of American Negroes at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, 1900. From American Monthly Review of Reviews 22, no. 130 (November 1900): 576. Photo: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001697152/

Essays

Article

In the Gallery: Introduction

“Introduction,” offers visitors a contemplative gloss on the exhibition’s broader themes through a quartet of moments: a quote, a work of contemporary art, and two versions of the same short film.

Article

What Is Black Cinema?

In this excerpt from their essay for Regeneration’s catalogue, the show’s cocurators, Doris Berger and Rhea L. Combs explore a question at the heart of the exhibition: What is Black cinema?

Article

Object Spotlight: Glenn Ligon’s Double America 2

Glenn Ligon’s (b. 1960) Double America 2 shows two Americas, one upside down.

Early Cinema, 1896–19152

Scroll To Explore