Music and Film

4

Music and Film4

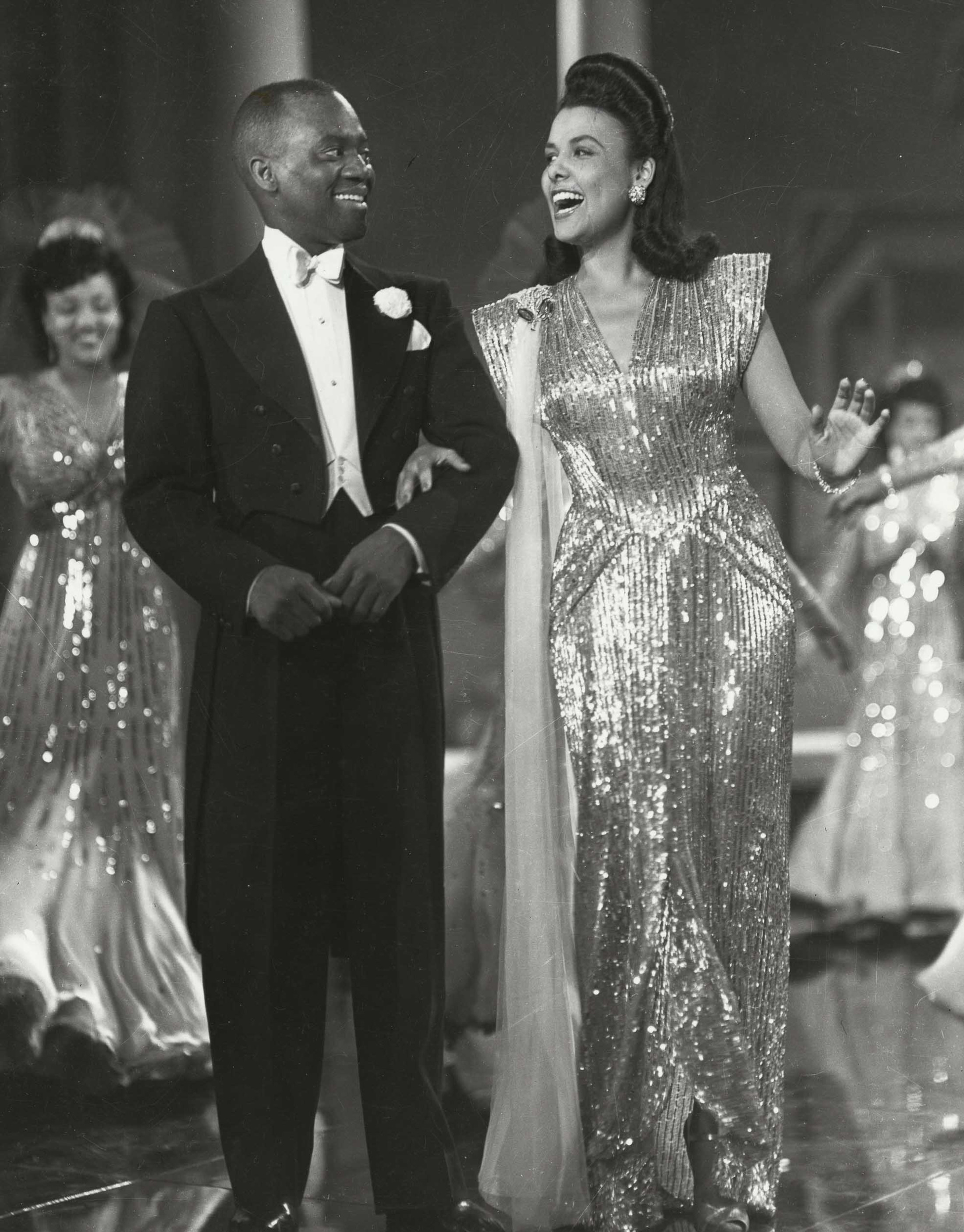

Fredi Washington (center) and Duke Ellington and his band in Black and Tan (1929). Core Collection, Production Files, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Theme Overview

The transition from silent to sound film in the late 1920s offered new opportunities to African American actors, dancers, singers, and musicians–many scouted from Harlem’s vibrant nightclub scene. Novel technologies like the “soundie” and growing international media markets brought with them expanded career horizons even as the range of characters and storylines available to Black talent outside of musicals remained limited. Highlighting the achievements of icons such as Duke Ellington and Hazel Scott, the “Music and Film” gallery illustrates how some performers navigated this changing landscape and found consistent work on and off the screen.

Featured Essay

Interlude: Black Europe

Scroll To Explore

During the 1920s and 1930s, a few Black performers left the United States and found more fulfilling careers in Europe. Paris, London, and Berlin (pre-1933) were entertainment hubs that offered spaces for cultural production that welcomed African American artists, entertainers, and intellectuals, and some of them became big stars. While Europe was not without racism and was entangled with colonialist power dynamics, there was no legal segregation, and Black entertainers were offered a wider spectrum of opportunities, even though they often had to navigate being exoticized and were performing for mostly white audiences.

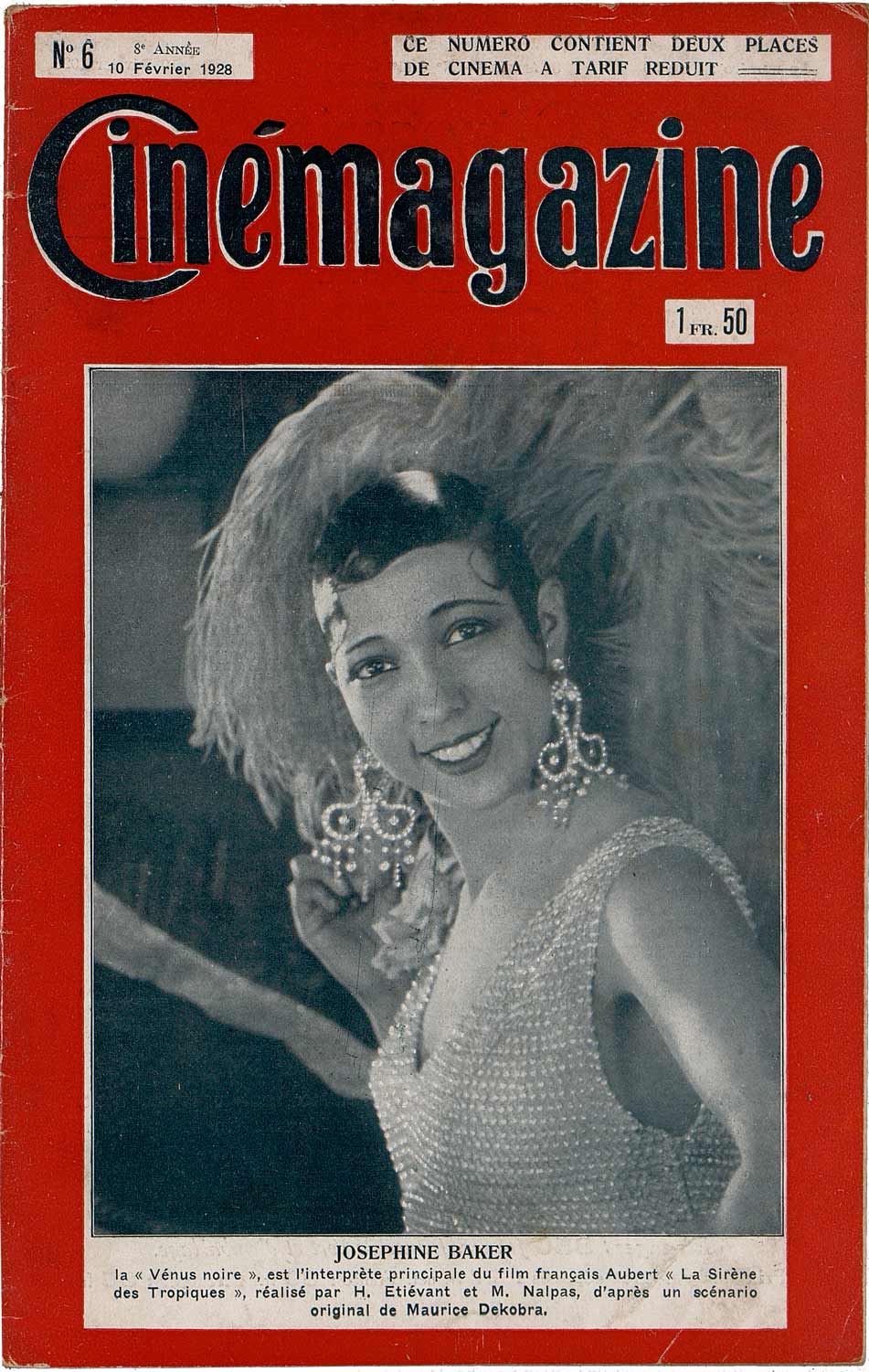

Cinémagazine, no. 6 (February 10, 1928) Cinémathèque Française, 79481

Despite fraught circumstances, entertainers like Josephine Baker and Nina Mae McKinney, the writers Richard Wright and James Baldwin, and jazz musicians including Arthur Briggs and Sidney Bechet found opportunities, especially in Paris, that they wouldn’t have had in the United States during that time. The presence of African Americans in Paris has often been understood as “a commentary on race,” as Tyler Stovall writes: “Some blacks left the United States expressly to escape the burdens of discrimination and came to Paris as self-conscious refugees from racism. . . . The myth of color-blind France is complex and flawed. Nevertheless it has exercised a powerful attraction upon both black Americans and the French themselves.” [1]

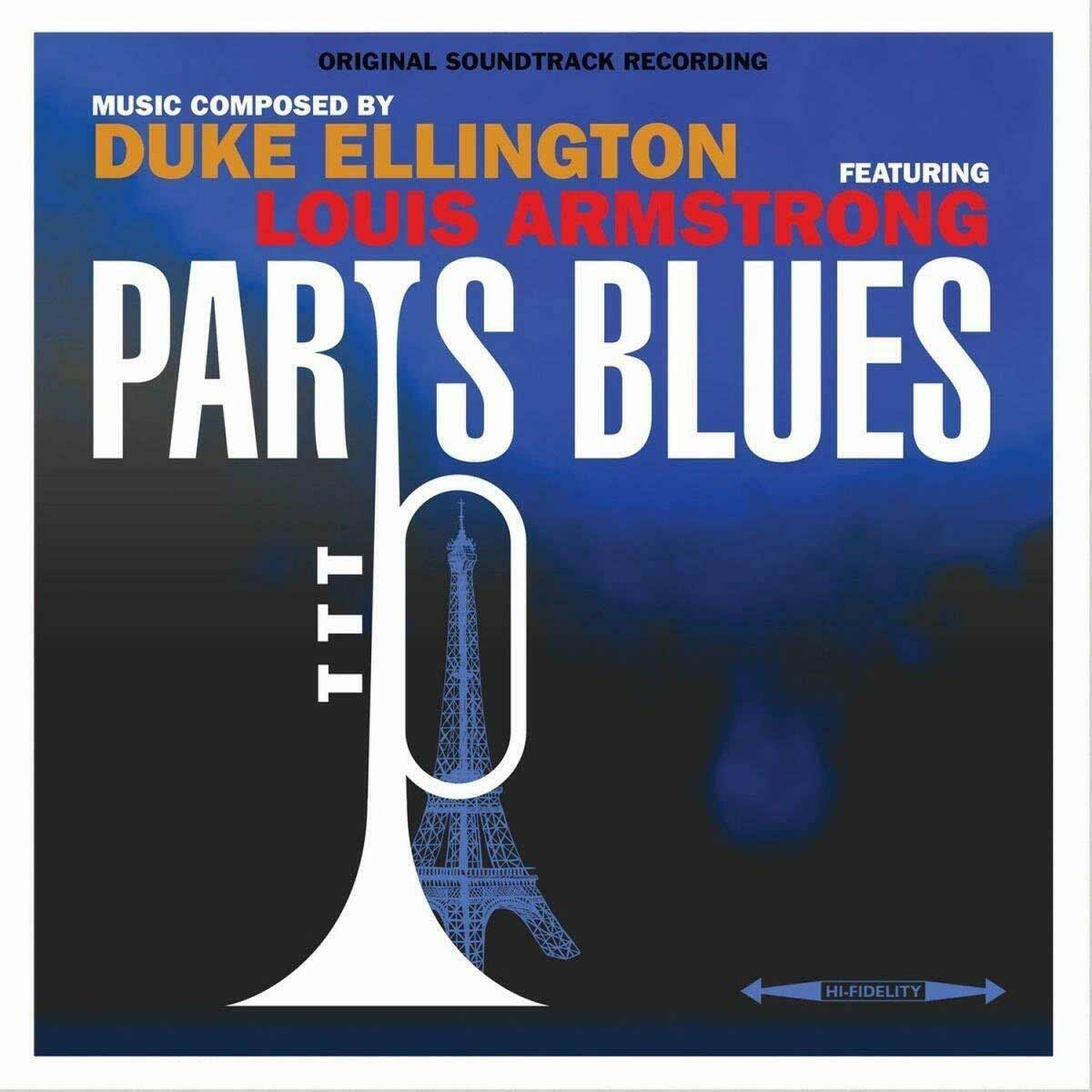

Paris Blues (1961), composed by Duke Ellington, soundtrack album. Photo courtesy of MGM Media Licensing and Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Black Hollywood

The period from 1910 through the 1940s in the United States was marked by world wars, race riots, and lynchings, but there were also periods of creativity and opportunity. In the entertainment business of the 1920s and 1930s, despite racial tensions and a depressed economy, many Black writers, musicians, and entertainers thrived even as they relied on white patronage for support or had to cater to all-white audiences in venues like the Cotton Club in Harlem. [2]

Mills Panoram, ca. 1939 ©Academy Museum Foundation. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures

Velma Middleton (left) and Luis Russell (right, at piano) with Louis Armstrong (center) and his orchestra in Swingin’ on Nothin’ (1942), production still

Sister Rosetta Tharpe in The Lonesome Road (1941), production still

With advances in moviemaking technology, particularly the introduction of “talkies,” the landscape of filmmaking shifted, and Black-cast movies grew in popularity. With the exception of Micheaux, many of the pioneering African American filmmakers were outpaced by the major studios in terms of budgets, especially as Hollywood started producing sound films that included entertainers and musicians like Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, and Lena Horne. Some of their appearances were designed strictly as musical interludes that have little to do with the film’s narrative arc, making it easier to remove them if there were issues (primarily

Doris Berger Doris Berger is vice president of curatorial affairs at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. She was previously a Getty postdoctoral fellow; a curator at the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles; and director of the Kunstverein Wolfsburg, Germany. Berger curated numerous art and film exhibitions, including Light & Noir: Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood, 1933–1950 (Skirball, 2014), and Isaac Julien: Baltimore (Academy Museum, 2022). She cocurated the Academy Museum’s inaugural exhibitions Stories of Cinema and Backdrop: An Invisible Art (both 2021). She is the author of Projected Art History: Biopics, Celebrity Culture, and the Popularizing of American Art (Bloomsbury, 2014). She has published essays in books and journals and has taught courses in art history, film, and gender studies in Austria and Germany.

Rhea L. Combs Rhea L. Combs is director of curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, where she is responsible for the exhibitions and conservation teams. She has curated numerous exhibitions nationally and internationally, including Now Showing: Posters from African American Movies (2019–21), Watching Oprah: The Oprah Winfrey Show and American Culture (2018–19), and Everyday Beauty: Photographs and Films from the Permanent Collection (2016–19) for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, where she previously served as supervisory curator of photography and film and director of the Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts. Her writings on African American cinema, Black women filmmakers, visual aesthetics, photography, and other topics have appeared in anthologies, academic journals, and numerous exhibition catalogues. She has lectured in the United States and abroad and has taught courses on visual culture, film, race, and gender.

Full essay available in the Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 exhibition catalogue, available for purchase at the Academy Museum Store.

[1] Tyler Stovall, Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996), xiii.

[2] The Cotton Club was originally Cafe Deluxe and owned by the heavyweight champion Jack Johnson. When Johnson suffered economic hardship, he sold the club to the gangster Owney Madden, who reopened it in 1923 with a new name. The club thrived during Prohibition, and its weekly broadcasts of its performances made it one of the most popular venues of the 1920s for its nearly all-white patrons. Its decor created a plantation-like atmosphere, with the mostly Black staff often presented as plantation residents, and the high-energy musical acts at times perpetuated stereotypical notions of African Americans. The Cotton Club nevertheless showcased some of the most widely known artists of the day, including Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, the Nicholas Brothers, and Ethel Waters. A dance club that was not segregated and had a thriving Black clientele was the Savoy Ballroom on Lenox Avenue in Harlem.

Essays

Article

In the Gallery: Music and Film

The transition from silent to sound film in the late 1920s offered new opportunities to African American actors, dancers, singers, and musicians–many scouted from Harlem’s vibrant nightclub scene

Article

Interlude: Black Europe

Doris Berger and Rhea L. Combs examine the intersection of emigration and entertainment in the careers of Black stars.

Article

Object Spotlight: Costume worn by Lena Horne

Horne refused to play stereotypes, and was often overlooked for more substantial roles or relegated to singing parts. She later used her public persona to become an outspoken civil rights activist.

Stars & Icons5

Scroll To Explore