Early Cinema, 1896–1915

2

Early Cinema, 1896–19152

Lime Kiln Club Field Day (1913, unreleased, reassembled 2014)

Theme Overview

“Early Cinema, 1896-1915” considers how the politics and popular culture of the dawning twentieth century influenced early Black cinema. Despite the ubiquity of racism, vaudeville performers like Sam Lucas and Bert Williams managed to craft noteworthy careers on stage and screen. But these professional successes often depended on performers’ willingness to incorporate racist tropes into their work, many Black artists appearing in blackface or taking subservient roles far beneath their skills and training. Many popular Hollywood films from this period offered a deeply distorted vision of America’s racial history and race-related power dynamics, such as D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), and even well-meaning stories like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) often perpetuated pernicious stereotypes. Artist Kara Walker highlights this latter tension in a large-scale silhouette work installed in the gallery, the first of second of four contemporary artworks on view in Regeneration.

Featured Essay

Bert Williams and Black Performance Culture

Scroll To Explore

In this excerpt from his essay for Regeneration’s companion volume, film curator Ron Magliozzi looks at the first Black superstar performer Bert Williams and the making of the 1913 film Lime Kiln Club Field Day.

When the Bahamian-born Bert Williams (1874–1922) and his African American partner, George W. Walker, began their entertainment careers together in 1896, it was a remarkably rich period of employment opportunity and creativity for Black artists in the United States; it was also a racially conflicted period. Faced with white audiences’ affection for demeaning minstrel stereotypes of racial inferiority rooted in nostalgic fantasies of prewar slave culture, a progressive-minded faction of the Black entertainment community struggled to raise consciousness. These entertainers’ desire to represent themselves authentically and to control the performance of race onstage led to the production of a once-lost film, known since its rediscovery in 2014 as Lime Kiln Club Field Day, which now stands as a testament to their determination.

Bert Williams and Odessa Warren Grey in Lime Kiln Club Field Day (dir. Edwin Middleton, T. Hays Hunter, 1913), film stills. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

In the first two decades of commercial film production, beginning in 1896, more than one hundred race-themed short films were released by US film producers, often using uncredited Black performers. But with titles such as A Watermelon Feast (1896), Dancing Darkey Boy (1897), On the Old Plantation (1901), Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or Slavery Days (1903), and The Chicken Thief (1904), these films consistently fed white audiences’ taste for tableaus of plantation life. Reviewing a Williams short released in 1916, a critic for the African American weekly Chicago Defender complained, “Moving picture directors know very little about what to do with the ‘brother’ on celluloid.”[1]

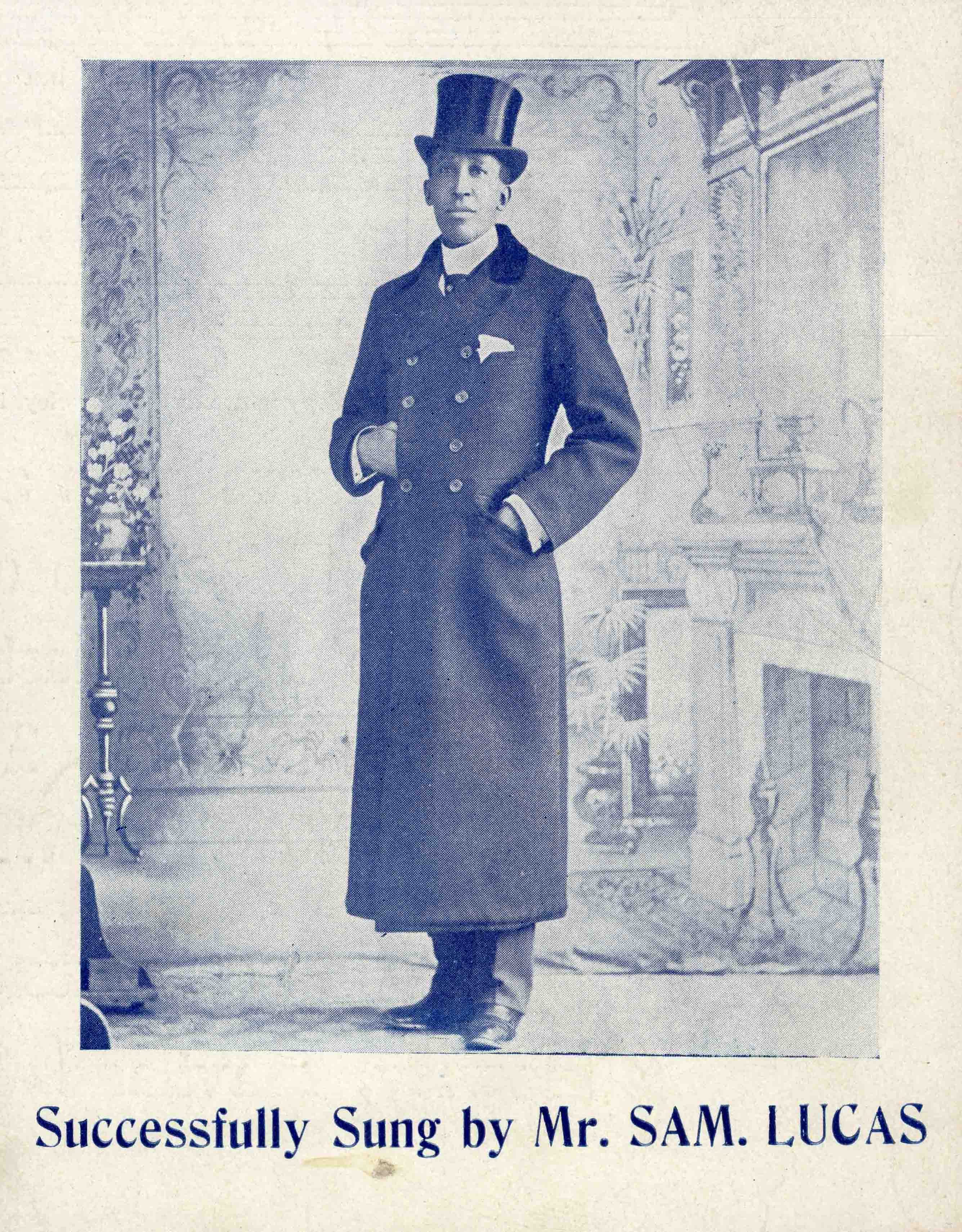

Sam Lucas, 1901, sheet music cover. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

Williams appeared as a solo act and the only Black performer with the Ziegfeld Follies. When Follies announced an alliance with the Biograph Company for the production of a Black-cast feature intended for interracial audiences, [2] Williams found himself with the opportunity to appear before the camera and bring a sizable company of African American performers with him. The cast of Black performers featured in Lime Kiln represented two generations of stage experience playing before multiracial audiences. Joining Williams were Abbie Mitchell, who would later sing in the premiere of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess (1935), Walker Thompson, who later appeared in Oscar Micheaux’s Symbol of the Unconquered (1920) and the sixty-five-year-old Sam Lucas, the pioneering “grand old man of the Negro Stage.” The leading lady Odessa Warren, who had performed in the chorus and designed costumes for Williams and Walker’s stage shows. After his death Williams was compared to Charles Chaplin. Both practiced a contemplative style of comic pantomime that served well for expressing pathos and were known to be intellectual in their private lives. Just so, before the camera in Lime Kiln, Williams is a thoughtful, self-motivated, and resourceful Black man who achieves the thing of most value in a romantic film: the loved one. The lingering close-up kiss between Williams and Warren that ends the footage shot for the film in a slow fade would have been among the boldest expressions of racial progress in popular entertainment at the time—had it been seen.

Bert Williams (bottom) and George Walker in a publicity photograph promoting In Dahomey, ca. 1903. Courtesy Museum of Modern Art.

What market there might have been for the benevolent depiction of African American life in Lime Kiln Club Field Day evaporated with the devastating impact of The Birth of a Nation when it was released in February 1915.

Full essay available in the Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 exhibition catalogue, available for purchase at the Academy Museum Store.

Ron Magliozzi is curator in the Department of Film at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Since he joined the museum in 1979, Magliozzi has organized gallery and theatrical exhibitions and headed special collections acquisitions. Film restoration projects include Lime Kiln Club Field Day (1913) and the Last Poets’ Right On! (1971). He served as chair of the International Federation of Film Archives Documentation Commission and edited the landmark book Treasures from the Film Archives: A Catalog of Short Silent Fiction Films Held by FIAF Archives (Scarecrow, 1988).

[1] “The Gambler,” Chicago Defender, August 5, 1916.

[2] In fact, it was the rising popularity of filmgoing that triggered Klaw & Erlanger’s announcement of their partnership with the Biograph Company for a series of 104 motion pictures exploiting stage plays and performers under contract to them, including Williams. Trade advertisement in Moving Picture News, June 21, 1913, reprinted in Kemp R. Niver, Klaw & Erlanger Present Famous Plays (Los Angeles: Locare Research Group, 1976), 36–37.

Essays

Article

In the Gallery: Early Cinema, 1896–1915

“Early Cinema, 1896-1915” considers how the politics and popular culture of the dawning twentieth century influenced early Black cinema.

Article

Bert Williams and Black Performance Culture

Film curator Ron Magliozzi looks at the first Black superstar performer Bert Williams and the making of the 1913 film Lime Kiln Club Field Day.

Article

Object Spotlight: Advertisement for Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Sam Lucas was one of the most celebrated entertainers of his time; he became the first Black actor to play the Uncle Tom character in a US screen version of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel.

Article

Object Spotlight - The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven

Walker’s artwork rejects mainstream narratives of a glorified old antebellum South, including depictions by white filmmakers well into the twentieth century.

Race Films3

Scroll To Explore