Freedom Movements

6

Freedom Movements6

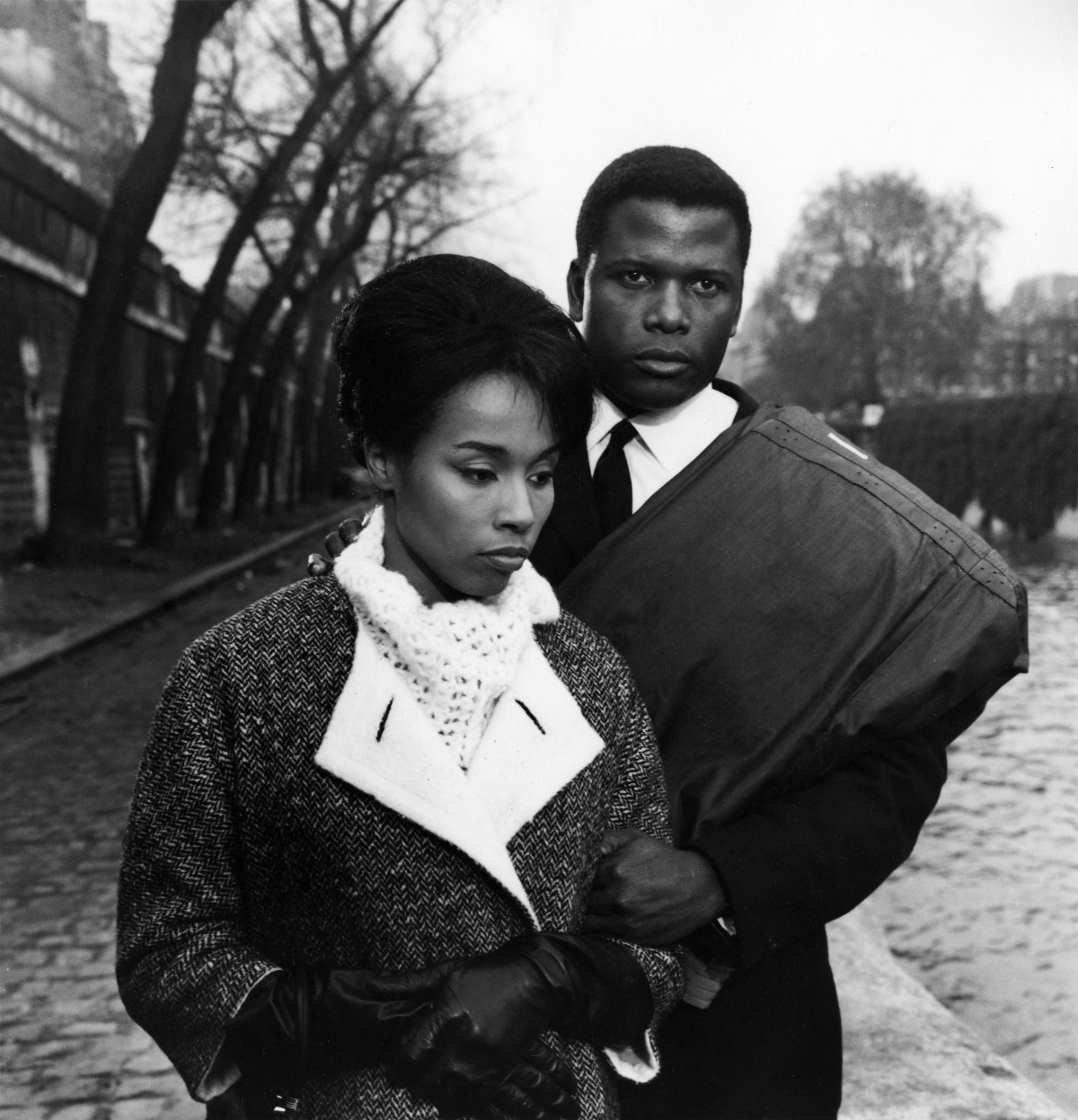

Sidney Poitier with Diahann Carroll in Paris Blues (1961). Photographer unidentified. Core Collection, Production Files, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Theme Overview

At the end of World War II, African American soldiers returning to the United States were asking pointed questions about equity and justice. Why fight fascism overseas only to come home to racial discrimination and segregation? Later, the triumphs of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were clouded by the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965 and 1968, respectively.

Postwar Hollywood reflected the changing times. As studio monopolies began unraveling and opportunities for independent cinema productions increased, more nuanced stories about racism and interracial relationships started to hit the screen. Black writers Lorraine Hansberry and James Baldwin were powerful voices during this period, using their pens to surface changing perspectives. Many Black actors such as Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, and Paul Robeson used their fame to promote civil rights causes on and off the screen.

Featured Essay

Paul Robeson

Scroll To Explore

In this excerpt from her essay for Regeneration’s companion volume, film scholar Ellen C. Scott examines the career of Paul Robeson and his difficulties maintaining control over his own image on screen. Perhaps no single figure embodies the promise and failure of Black actors in the American cinema more fully than Paul Robeson (1898–1976). Robeson powerfully marshaled his own image in his performances, especially in song, often altering the lyrics of white-authored tunes to sharpen their racial critique and elide their racist caricatures.[1] Controlling one’s cinematic representation was a far more slippery proposition, however. Robeson appeared in only twelve films throughout his long career as a public figure and entertainer, a fact that reflects the difficulties he encountered in establishing control over images that others directed, and that speaks more generally of the challenges of presenting a fluid and nonexploitative image of African American manhood on the American screen.[2]

Paul Robeson and Hattie McDaniel in Show Boat (1936), production still. Courtesy Margaret Herrick Library.

Robeson began his film career in the race film system with Oscar Micheaux’s Body and Soul (1925), in which he played an evil preacher and an inventor, a portrayal that caused consternation in the Black press.[3] Robeson’s next films represent more collective experiments with the medium, appearing as the biracial French writer Alexandre Dumas in an amateur film (1926) by Ralph Barton, a cartoonist and graphic artist, and with Borderline (1930), an interracial avant-garde production that featured Robeson with his wife and business manager, Eslanda Goode Robeson. In 1933 Robeson made his first Hollywood film, Emperor Jones, which raised important issues about Black imprisonment and the prospect of Black self-rule in a world in which white colonialism dominated. In 1936 he appeared in Showboat as Joe, a role he had made famous on the stage. Here Robeson offered his famous rendition of “Old Man River” in an expressionistic sequence.

Eslanda Goode Robeson (standing), Paul Robeson (center), and Lawrence Brown (right) in Big Fella (Great Britain, 1938), production still. Courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, NYPL.

Robeson’s six British films represent a chapter in his career in which he made important contributions in representing the Black international on-screen. In Dark Sands (1937), perhaps the best of these films, he plays Jericho, a talented and rebellious medical student turned World War I soldier, who becomes a fugitive from the law who dedicates himself to doing good and saving lives. With this film, Robeson finally played a role with the stature he had long strived for. Such a role was an important counterpart to the American cinema’s Black characters. In a win for nomadism, exile, freedom, and Black self-determination, however, Robeson convinced the filmmakers to end the film with Jericho continuing to evade authorities.[4]

Dark Sands (Great Britain, 1937), theatrical release poster

In 1942 Robeson starred in his last Hollywood film, Tales of Manhattan. He had been assured by his friend Boris Moros, a Hollywood leftist and the film’s musical director, that it was a solid project that revealed the power of collective organizing and communal ownership. The film, however, situated Black people not in Manhattan but in a rural outpost, which so offended some African Americans that they threatened to picket. An embarrassed Robeson, again foiled by editing and the larger narrative arc into which his image was enlisted, said he would join the picket lines if they formed in New York. By 1943 he had essentially retired from film acting.

Paul S. Henderson (photographer), Paul Robeson (second from left) and members of the Baltimore chapter of the NAACP protest the racial segregation of Ford’s Theatre, 1948. Courtesy Maryland Center for History and Culture Library.

Full essay available in the Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898–1971 exhibition catalogue, available for purchase at the Academy Museum Store.

Ellen C. Scott is associate professor of cinema and media studies and associate dean of the School of Theater, Film and Television at UCLA. Her research focuses on the meanings of media in African American communities and the relationship of media to the struggle for racial justice and equality. She is the author of Cinema Civil Rights: Regulation, Repression, and Race in the Classical Hollywood Era(Rutgers University Press, 2015). She is currently working on two projects, one exploring Black women film critics and another examining the history of slavery on the American screen, which has received a grant from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Academy Scholars program.

[1] Shana Redmond, Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 102.

[2] For more on Robeson’s career and activism, see Shana Redmond, Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020),and Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography (New York: Open Road Media, 2014).

[3] See Maybelle Chew, “Along the White Way,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 11, 1926. Charlene Regester also discusses the trouble that censors, Black and white, had in New York with the film’s depiction of the minister played by Robeson. Regester, “Black Films, White Censor,” in Movie Censorship and American Culture, ed. Francis Couvares (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996), 180–81.

[4] Scott Allen Nollen, Paul Robeson: Film Pioneer (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010), 116–17.

Essays

Article

In the Gallery: Freedom Movements

“Freedom Movements” surveys this shifting terrain through a range of documentary and narrative feature materials and case studies.

Article

Paul Robeson

Film scholar Ellen C. Scott examines the career of Paul Robeson and his difficulties maintaining control over his own image on screen.

Article

Object Spotlight: Some Remember Sock Hops, Others Remember Riots

In this piece, artist Theaster Gates (b. 1973) comments on the stark racial disparities of the civil rights era

Article

What He Witnessed: Blackness, Film Spectatorship, and James Baldwin’s The Devil Finds Work

Film scholar Michael Boyce Gillespie looks at James Baldwin’s writing on Black film and how it served as a culmination of his long deliberation on race and America.

Article

William D. Alexander: All-American

Award-winning documentary filmmaker Shola Lynch traces the career of pioneering documentary and feature filmmaker William D. Alexander

Agency7

Scroll To Explore